Contagious Diseases in Chinchillas

Chinchillas themselves are an exceptionally clean, healthy, and low-risk pet to have. As long as the chinparent is meticulous about maintaining the cleanliness of their cage environment and the freshness and quality of their supplies, especially edibles, then the chances of infectious disease are very low. This section lists some of the diseases they can contract that are potentially transmittable to other chins and humans. Herpes, Rabies, Monkeypox, and Frenkelia Microti Infection are very rare but are mentioned because there have been cases involving chinchillas. This list is NOT all-inclusive .

Ringworm Fungus and Giardia

Ringworm fungus and Giardia are the most common conditions that chinchillas can contract which are transmittable to humans.

Pasteurella

By DVM Glikis-Scott (was Fernandez) of the Birmingham Veterinary Clinic, MI:

Pasteurella in both rabbits and chinchillas is a frustrating thing to treat. There is no cure, we try to manage the infection through a combination of surgical drainage of abscesses and antibiotic therapy; often times very long courses of antibiotics. Pasteurella can be a dormant infection, especially in rabbits. It is present in the nasal passages of most rabbits and a combination of stress, poor nutrition, etc., can bring about an active infection. It is transmissable when animals are in contact with nasal secretions, pus, etc. Pasteurella also naturally resides in cat saliva.

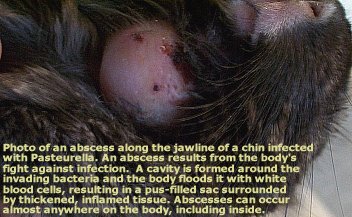

Warning symptoms are respiratory problems, eye infections. In chinchillas, jaw and tooth root abscesses can occur and when this happens they are given a very poor prognosis; they seem much less tolerant of Pasteurella infections compared to rabbits. If the infection is mild, i.e., sneezing and small amounts of nasal discharge, antibiotics can be helpful. I use Baytril and sometimes a combination of Baytril and Penicillin in rabbits. Generally speaking, if the infections creates abscesses, the prognosis is far poorer. The abscesses can be drained but they typically reform or new ones develop as in the jawline, often leading to osteomyelitis (infection of the bone). I have seen this in chins and the outcome is very bad. The chinchilla becomes very toxic as a result of the overwhelming infection.

In milder cases of infection (upper respiratory infections) even when an animal responds to antibiotics, I always warn owners that the potential exists for the infection to return at some point because it is never truly cured. The bottom line is that Pasteurella is difficult to treat in rabbits, chins and guinea pigs, however chins seem to carry the worst prognosis when they present with this disease.

Article Submitted By A Veterinary Technician With Case Experience:

Signs of Pasteurella include abscesses internally and/or externally (especially along the jawline) and/or respiratory infection, which in turn causes runny nose, goopy eyes, etc. An animal can be infected with Pasteurella and never show symptoms but still be a carrier of the disease.

Symptoms can be brought on by stress, a compromised immune system, etc. Pasteurella is spread through bodily fluids, like saliva and urine. So if a chin shares a water bottle, if they spray into another cage or if you hold a sick chin in another room and it sneezes on you, then you go hold another chin, that’s cross-contamination. Rabbits carry Pasteurella normally, which is why they should never share exercise time with chins. Cavies (guinea pigs) can also contract Pasteurella. Pasteurella may go dormant but it is incurable.

From Medical Microbiology By Frank M. Collins:

Clinical Manifestations: In cattle, sheep and birds Pasteurella causes a life-threatening pneumonia. Pasteurella is non-pathogenic for cats and dogs and is part of their normal nasopharyngeal flora. In humans, Pasteurella causes chronic abscesses on the extremities or face following cat or dog bites.

Structure, Classification, and Antigenic Types: Pasteurellae are small, nonmotile, Gram-negative coccobacilli often exhibiting bipolar staining. Pasteurella multocida occurs as four capsular types (A, B, D, and E), and 15 somatic antigens can be recognized on cells stripped of capsular polysaccharides by acid or hyaluronidase treatment. Pasteurella haemolytica infects cattle and horses.

Pathogenesis: Human abscesses are characterized by extensive edema and fibrosis. Encapsulated organisms resist phagocytosis. Endotoxin contributes to tissue damage.

Host Defenses: Encapsulated bacteria are not phagocytosed by polymorphs unless specific opsonins are present. Acquired resistance is humoral.

Epidemiology: Pasteurella species are primarily pathogens of cattle, sheep, fowl, and rabbits. Humans become infected by handling infected animals.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis depends on clinical appearance, history of animal contact, and results of culture on blood agar. Colonies are small, nonhemolytic, and iridescent. The organisms are identified by biochemical and serologic methods.

Control: Several vaccines are available for animal use, but their effectiveness is controversial. No vaccines are available for human use. Treatment requires drainage of the lesion and prolonged multidrug therapy. Pasteurella multocida is susceptible to sulfadiazine, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline.

Pneumonia (respiratory infection)

Be aware that sometimes chins are just clearing their nose and this can result in some watery nasal discharge and nose-wiping. A sensitivity to dust or hay or some particle inadvertently inhaled can result in the nose-clearing sound which is distinctly different from the sneeze; it is a brief, voluntary expulsion of air through the nose as opposed to an involuntary “Ahh-choo” sound. If you are at all uncertain as to whether the chin is sneezing or clearing his nose, and if the wetness around the nose or the nose-clearing sound lasts more than a day, take your chin to your exotics specialist vet for immediate examination.

By Companions Animal Hospital:

Respiratory diseases are often seen in pet chinchillas. The respiratory problem can easily become pneumonia. Conditions such as overcrowding, poor ventilation, and high humidity may predispose to pneumonia. Common signs include lack of appetite, lethargy, difficulty in breathing, nasal discharge, and swollen lymph nodes.

By Susan Brown, DVM, Midwest Bird & Exotic Animal Hospital:

Pneumonia is another common condition observed in chinchillas which are caused by a number of disease agents. Bordetella, Pasteurella, Pseudomonas, and E. coli are a few of the bacterial species commonly associated with the syndrome. Damp, drafty housing often predisposes the pet to this condition. Clinical signs include discharge from the eyes and nose, loss of appetite, and rough hair coat. Death may result from this respiratory disease. Treatment involves supportive care and antibiotics.

Rabbit Viral Hemorrhagic Disease (VHD)

Although this disease is usually listed as being only contagious between and contractible by rabbits, we know of a case that affected chinchillas which had been kept in a household that had rabbits. These chinchillas appeared normal and healthy when they were relocated to another herd, then shortly afterward the rabbits, the relocated chinchillas, and almost half the herd they were relocated to suddenly manifested symptoms and abruptly died of VHD. Veterinary autopsies revealed the presence of the VHD calicivirus, so it must be noted that this disease IS a risk for chinchillas, that it is highly contagious, may not be treatable and is usually lethal to those it infects.

Ectoparasites: Lice, Mites, Ticks, Fleas

Fur density does NOT protect chinchillas from getting lice, mites, ticks or fleas because these pests can affect the face and ears where the fur is less dense, causing wart-like lesions and possibly anemia. We know of one case at a chinchilla rescue where both fleas and flea bites were observed on a chin’s back, where the fur is densest. We know of another case where the chins’ ears were covered in flea bites and one chin had scratched a hole in his ear from the constant itchiness; those chins were also anemic. Chinchillas are also vulnerable to biting lice and blood-sucking mites.

Chinchillas Unlimited has an article on the subject of ectoparasites, some select quotes: “Chinchillas are only transient hosts for fleas – but they can get mites and ticks (around the facial/ear area more commonly)… Mites are generally host (and food) specific. Some cause agricultural concerns (red spider mite for instance) – others are a health hazard – causing allergies (respiratory), skin conditions (mange and dermatitis, etc)… Ticks are a different matter altogether – and generally require blood as a food source as part of their life-cycle – therefore they bite!! It is possible for the disease to be passed on by tick-bites…”.

Also see: An Outbreak of Listeriosis in a Breeding Colony of Chinchillas (.pdf) -and- Incidence of Listeriosis in Farm Chinchillas (Chinchilla laniger) in Croatia (.pdf)

Introduction

Listeriosis is one of the more common diseases of chinchillas, causing death at any age. It is a common infection in many other animal species (i.e., mice, rats), both domestic and wild in many parts of the world. The organism can also infect man. Hence, care should be taken when handling infected animals or when in an infected environment to avoid ingesting the bacteria.

Cause

Listeriosis is caused by a small, gram-positive rod-shaped bacteria called Listeria monocytogenes.

Transmission

The bacteria may be introduced into a herd by the introduction of infected chinchillas, by contact with another animal species, or by contaminated feed. The feed may be contaminated while in the barn (ie: open feed bins), or the hay may be contaminated in the field prior to processing (ie: mice). Chinchillas usually acquire the infection orally. Once a chinchilla is infected with the bacteria it is passed in the feces. Therefore equipment, cages, feed, and water contaminated with the infected feces are the most important factors involved in the spread of the disease to other chinchillas within the herd.

Disease

Sickness due to listeriosis is slow in onset with slow spread throughout the herd. There may be one death followed by the death of another chinchilla in 5-6 months; the affected animal will lose weight and condition. Diarrhea may be noted, however, constipation is more common. Straining may result in prolapse of the rectum. Less frequently, chinchillas may show blindness or nervous signs (ie: convulsions, head tilt), if the bacteria invade the brain. Eventually, the chinchillas appear to be in pain and will move only if urged. They may stop eating but continue to drink water. They may grit their teeth and vocalize. This occurs a day or so prior to death.

Postmortem Lesions

The most common finding is the presence of pin-point white spots throughout the liver. These areas of dead tissue are sometimes also seen in the spleen, bladder, and intestinal wall. Examination of the intestinal content often reveals constipation with the presence of scant, hard, dry ingesta.

Diagnosis

A presumptive diagnosis can be made based on history and postmortem findings. Listeria bacteria can be readily isolated from the liver of chinchillas with typical postmortem findings. A diagnostic laboratory can identify the bacteria and determine what antibiotics would be useful for treatment. This is important since some bacteria may be resistant to certain commonly used antibiotics (ie: tetracycline).

Treatment

Antibiotics including tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and penicillin [penicillin should NEVER be given to a chinchilla under any circumstances!] have been reported to be useful, however, the disease must be treated at an early stage. Chloramphenicol may cause infertility hence should be avoided in breeding animals. Tetracycline may be fed orally at the rate of 25 mg/ounce of drinking water, and chloramphenicol at the rate of 10 mg/ounce of water for at least 5 days. All animals may not respond. Note that animals which appear to recover may remain carriers of the bacteria.

Prevention and Control

Good management practices, especially sanitation, are the best means of preventing listeriosis. This includes a thorough cleaning and disinfecting of cages, water bottles, and sand baths. The introduction of new stock should be chinchillas from known healthy sources. These chinchillas should initially be raised in complete isolation from the rest of the herd. Chinchillas with listeriosis should be treated with antibiotics as soon as possible. Isolation of such animals is ideal to prevent spread within the herd. All badly affected chinchillas should be removed (culled) and euthanized.

Bordetella Bronchiseptica

What we know of Bordetella bronchiseptica and how it relates to chinchillas derives from many hours of research on the disease in general, and from consultation with vets, testing labs, and those who’ve had direct experience with it.

Bordetella bronchiseptica is a “small, gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium of the genus Bordetella” (ref– wikipedia.com), and is one of several strains of Bordetella. This particular strain affects chiefly animals and is transmittable between species; human infection is possible but usually limited to immuno-compromised individuals. Bb is a respiratory pathogen and can be either a primary or secondary infection source.

Bordetella bronchiseptica is known to afflict many species, including: pigs, monkeys, sheep, goats, guinea pigs, rats, rabbits and horses, but it is most common to dogs, where it is referred to as “kennel cough,” and cats where it can lead to bronchopneumonia. Bb is relatively rare in chinchillas, but when active this bacterial infection manifests in symptoms that appear like pneumonia or bronchitis: hacking, sneezing, respiratory distress, nasal discharge.

Bordetella bronchiseptica is very fast acting and lethal to chinchillas, especially if not treated immediately and vigorously, and it is can be lethal despite treatment. It’s extreme level of contagion cannot be stressed enough as this bacteria is airborne, i.e., not spread through direct contact alone:

“Though it [Bordetella bronchiseptica] is commonly known to colonize in respiratory tracts of animals, it can also withstand surviving long-term in the environment, a trait that separates it from its most common relatives…”

(ref– microbewiki.kenyon.edu)

“B. bronchiseptica also differs from the other subspecies in its ability to survive nutrient limiting conditions, at least in vitro, suggesting that in addition to transmission by the aerosol route, this organism may be able to transmit via environmental reservoirs (Porter et al 1991, Porter and Wardlaw 1993).”

(ref- felinebb.info: see Disease Info, then Pathogenesis)

“Bordetella bronchiseptica is a commensal in the upper respiratory tract of dogs, cats, swine, rabbits, horses, guinea pigs, rats, and possibly other animals. Infections may be endogenous or exogenous. Inhalation is the principal mode of infection. Spread is by direct and indirect contact and fomites.”

[Fomite= “an inanimate object or material on which disease-producing agents may be conveyed” (ref– medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com)]

(quote– book: “Essentials of Veterinary Bacteriology and Mycology” by Gordon R. Carter, Darla J. Wise, 2004, p. 116)

“Both viral and bacterial [Bordetella bronchiseptica being the bacterial infection] causes of kennel cough are spread through the air by infected dogs sneezing and coughing. It can also spread through contact with contaminated surfaces and through direct contact. It is highly contagious, even days or weeks after symptoms disappear.”

(ref– wikipedia.org: Kennel Cough)

It is quite probable that this disease can be carried in chinchillas asymptomatically, that is, a chinchilla that survives Bordetella may recover and show no symptoms but may still be carrying the pathogen in a dormant, as opposed to active state. We know of one reported case where a chinchilla Bordetella survivor experienced a recurrence of the disease and other animals, cats, in particular, can be asymptomatic carriers:

“In many species, Bb is an opportunistic pathogen. The same is probably true in cats. Long-term asymptomatic carriage commonly occurs in cats (Coutts et al 1996). Shedding of Bb can be triggered by a variety of environmental factors. Stressful conditions are a common cause of the development of the opportunistic disease.” (ref– nobivacbb.com)

Culture tests are still the most common method of testing for Bordetella bronchiseptica, but the bacteria can be hard to grow in culture, according to our exotics specialist vet. The comparatively new method of PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) testing is an improvement over that: “The conventional method of detection, by culture, is specific but lacks sensitivity. It also takes 3 to 7 days to obtain a result. Current serological tests do not differentiate the closely related Bordetella species. Only molecular detection by PCR can give both rapid and specific identification of B. bronchiseptica.” (ref– zoologix.com)

A PCR test can identify the Bordetella bronchiseptica pathogen in chinchillas (ref– wikipedia.com), we verified this by contacting two testing laboratories: Zoologix, Inc. (ref) and Clongen Laboratories (ref). According to our communication with Zoologix, Inc., a laboratory that specializes in PCR testing, a respiratory swab (from the nasopharynx, or throat) is the preferred sample from which to do PCR testing for Bordetella bronchiseptica in chinchillas. If symptoms are nasal or ocular in an active case, then swabs from those areas would also be useful. PCR testing can be effective in detecting the pathogen inappropriate samples from asymptomatic carriers.

Because there is the potential for a chinchilla to carry Bordetella bronchiseptica asymptomatically with the possibility of becoming active and infectious again in the future, and because the disease is so contagious and deadly to chinchillas when a case is active, we believe that it is absolutely necessary to declare the place where an outbreak has occurred under quarantine until all infected chinchillas have been submitted for and cleared by PCR testing.

References and Additional Reading

- Zoologix, Inc.

- Microbe Wiki

- Wikipedia

- McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Bioscience

- School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison

- ref– book: “Essentials of Veterinary Bacteriology and Mycology” by Gordon R. Carter, Darla J. Wise, 2004, pp. 116-118

These sites have a particular focus, but also contain general information about Bordetella Bronchiseptica:

Bordetella bronchiseptica and its treatment in chinchillas is not new news, cases have been reported since at least the mid 1990’s. The following article was written by a pet breeder and rescuer who has also worked as a veterinary technician. It is a summary of information gathered from pet breeders and ranchers in the U.S. and Canada who had experience with the disease:

“Bordetella is a zoonotic airborne gram-negative bacteria that can be catastrophic to chinchillas. Unfortunately, there are not excessive amounts of research regarding this highly infectious disease but the evidence left from infected herds both large and small rarely leaves many survivors, and any long term effects in any surviving animals have not been determined, although some of the few seem to have no lasting effects if they make it through the infection.

“Symptoms of Bordetella are very similar to those of a basic upper respiratory infection and pneumonia although the cause is different and must be treated accordingly. Symptoms include wheezing, rattling, fluid in the lungs, runny nose and/or eye, fluid in the ears, sneezing, and coughing. Left untreated Bordetella is fatal, and even with extensive treatment recovery is not guaranteed. All, some, or none of the symptoms may be expressed, there does not appear to be any set pattern in which symptoms will or will not show, or for how long.

“Animals that show symptoms or test positive for this should be immediately separated to help prevent any further infection. Separation should include different structures with different ventilation systems. Separation within the same structure will not prevent the spread as it will easily travel through air ducts, under doors, and on air currents. Cleaning with bleach and water has appeared to not be helpful in preventing the spread once the disease is active.

“Certain conditions will help spread the disease quickly and allow the bacteria to flourish, these include crowded areas, same cages with poor ventilation through them, poor ventilation in the housing structure, high humidity, and poor house keeping practices. Like most bacteria it grows in moist, warm conditions.

“Full treatment is critical in treating Bordetella. A course of antibiotics must be run for 14 days to fully get rid of the disease and prevent re-occurrence from the same bacteria. The best known way to treat Bordetella is with Baytril (injectable is the best route for Baytril) twice per day. Due to the effects that such strong antibiotics have on the chinchillas digestive system hand feeding may be required, which is why it’s advised to always keep Critical Care on hand, you will never know when you will need it!

“If bloat is a concern to your chinchilla while treating you can use 1 full dropper of simethicone every four hours to help reduce gas build-up. If the chin is eating or being hand-fed enough this should not be necessary. Probiotics are needed to help replenish the good bacteria in the digestive system. Probiotics should be given at least two hours after antibiotics to prevent them from canceling each other out.

“Summary: Bordetella has been a contributing factor in wiping out entire herds of more than 200 animals. The results are almost always fatal with less than 10% known survival rate. A full course of treatment is very important to prevent the return of various and inconsistent symptoms. It can be transferred to and from chinchillas and other species including, but not limited to: humans, cats, dogs, other chinchillas, and more. It is airborne and highly contagious.”

Human Herpes Virus

From “Spontaneous human herpes virus type 1 infection in a chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera f. dom.)” by P. Wohlsein, A. Thiele, M. Fehr, L. Haas, K. Henneicke, D. Petzold, W. Baumgärtner for Acta Neuropathologica

Note by ChinCare: Herpes in chinchillas is extremely rare, humans with Herpes should take special precautions when interacting with their chin.

A 1-year-old male chinchilla with a 2-week history of conjunctivitis suffered subsequently from neurological signs comprising seizures, disorientation, recumbency, and apathy. After 3 weeks of progressive central nervous disease, the animal was killed in view of the poor prognosis. Non-suppurative meningitis and polio encephalitis with neuronal necrosis and intranuclear inclusion bodies were observed at necropsy and by light microscopy. The brain stem and cerebral cortices were most severely affected. Both eyes displayed ulcerative keratitis, uveitis, retinitis and retinal degeneration, and optical neuritis. Additionally, purulent rhinitis with focal erosions, epithelial degeneration, and intranuclear inclusion bodies was present.

Ultrastructurally, herpes virus particles were detected in neurons of the brain. Immunohistochemistry with antisera specific for human herpesvirus types 1 and 2 resulted in viral antigen labeling in neurons, glial cells, and neuronal processes. Viral antigen was found in the rhinencephalon, cerebral cortices, hippocampus, numerous nuclei of the brain stem, single foci in the cerebellum, and in a solitary erosive lesion of the right nasal vestibulum. Viral antigen was not detected in the eyes. The virus was isolated from the CNS, and nucleic acid sequence analysis of the glycoprotein B and the DNA polymerase revealed a sequence homology with human herpesvirus type 1 of 99% and 100%, respectively. The clinical signs, the distribution of the lesions, and the viral antigen suggest a primary ocular infection with subsequent spread to the CNS. Chinchillas are susceptible to human herpesvirus 1 and may play a role as a temporary reservoir for human infections.

Rabies and Monkeypox

Rabies documented in MA and OH

“Between September 1992 and September 2006, more than 47,000 animal specimens have been submitted to the State Laboratory Institute (SLI) for rabies testing. Of these specimens, more than 4,400 have tested positive for rabies. Positive animals include more than 2,500 raccoons, 1,400 skunks, 340 bats, 125 cats, 125 foxes, and 80 woodchucks. Other species that have had at least one animal test positive in Massachusetts include cow, dog, horse, pig, otter, fisher, goat, chinchilla, shrew, rabbit, and deer.” (ref- .rtf, mass.gov)

In Ohio, the Rabies Testing and Percent Positive spreadsheet declared 5 chinchillas testing positive for rabies from 1980-2002. (from a now archived report by the Ohio Dept of Health)

Monkeypox (from a now archived report by the WI Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection)

This orthopox virus can be transmitted to humans and was first found in the Western Hemisphere during a Wisconsin outbreak in May and June 2003. While farm animals are generally not susceptible to monkeypox, farm-raised rabbits and chinchillas may get the disease.

Frenkelia Microti Infection in a Chinchilla (Chinchilla Laniger) in the U.S.

Archived USDA article by: Dubey, Jitender/ Clark, T – Naval Med Center, CA/ Yantist, D – Armed Forces Inst, DC

Parasites of the genus Frenkelia are single-celled parasites of rodents, small mammals and birds. Rodents become infected by ingesting feces of infected birds and birds become infected by eating rodent tissues. Scientists at the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center and the U.S. Naval Medical Center, San Diego, California report for the first time Frenkelia infection in the brain of a chinchilla and suggest that the same parasite causes hepatis in chinchillas. The results will be of interest to biologists, parasitologists, and pathologists.